Outsourced: Globalization, Textiles, and The South Coast [Pt.1]

This blog is part one of a series covering the history of the South Coast’s textile industry and the downstream impacts on labor, social capital, and community cohesion. Always home to dynamism, innovation, grit, and resilience, the South Coast continues to push forward. From whaling and textiles to fishing and now offshore wind, we have seen booms and busts, we may get knocked down, but we always get back up.

This series is the story of one of those cycles, shining a light on the underbelly of globalization and stripping away the abstract financial metrics often used to whitewash its impacts. It is a story of loss and decay, but also of endurance and resilience, and as the South Coast looks ahead with its continuing fishing industry, growing creative class, and burgeoning offshore wind industry, it is a story of renewal.

I’m Dan Moriarty, Groundwork’s newest community coordinator. I am a South Coast native who has always been interested in history, especially local history. This series is adapted from a research paper written during my Master’s in Political Science at Florida Atlantic University. My research niche is looking at how geography and technology influence the development of states and political cultures. As a local, I’m very excited to share this series with my community. As Groundwork’s Community Coordinator (and EforAll’s Program Coordinator), I’m just as excited to help support the South Coast in continuing its history of innovation and industrial vitality.

Introduction

The economy of the United States at one point in time could provide a family with a meaningful life on a single income. Now, for many, it can barely provide a stable job – let alone a home. Where the U.S. once exported manufactured goods around the world, toward the end of the 20th century, it began to resemble an extractive economy. The top exports from Japan to the United States in 1980 were cars, tractor chassis, trucks, electronics, and motorcycles. In contrast, the leading exports from the United States to Japan were soybeans, corn, coal, wheat, and cotton.

Now, large swaths of the U.S. economy rely on the high-tech and financial speculation industries, resulting in a vaporware-like economy that produces little material and is overreliant on other nations for imports of everything from medicine to hardware. Outside of the lucky few who make it through college and land jobs in tech and finance, many Americans default to low-wage, low-to-no-benefit service sector jobs, selling cheap imported goods on behalf of multinational corporations. Unionization, wage-to-productivity, and wealth equality are at all-time lows, and even the paradigm of the wage laborer is shifting into the gig economy.

Rust

The undercurrent of this situation is a long decline in manufacturing in the United States, leaving behind dilapidated factories, rudderless workers, weakened or destroyed unions, and the depopulation of small cities. As the factories go, local capital constricts, and restaurants, shops, and other small businesses follow suit.

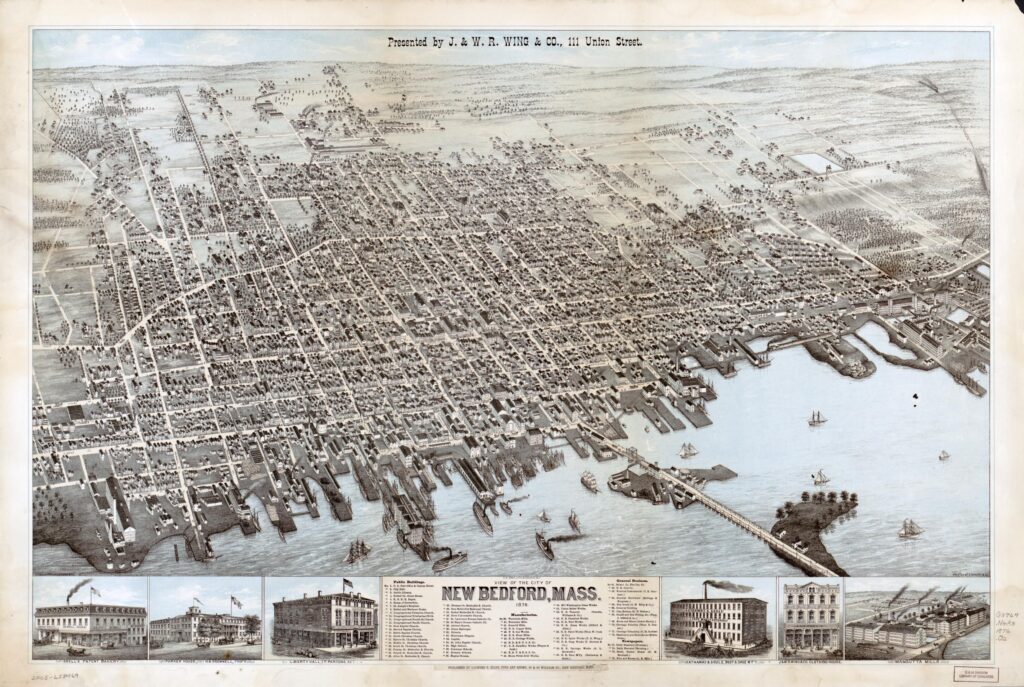

Much of the interest in deindustrialization shown by political scientists and economists has focused on Appalachia and Michigan’s steel and automotive industries. Far less attention is paid to the earlier decline of New England’s textile industry. The mill cities of New England were the first casualties in a tectonic shift in the American and global economies. The capital mobility strategy that would define Neoliberal globalization was born in the textile industry of New England. Perhaps nowhere in New England is this as clear as in my home, the “South Coast” region of Massachusetts.

The Rise of New England’s Textile Industry

As early as 1643, in-home textile manufacturing was occurring in Massachusetts. Wooden looms, situated in basements or barns, produced homespun textiles typically spun by the daughters and wives of farmers. Like the produce of their farms, the textiles were produced for self-sufficiency or sold locally to their neighbors. While the affluent of New England imported fine textiles from Europe, its working class acquired theirs through home weaving or local purchase. Slowly, localized textile trading began to grow. Before the American Revolution, the shared hostility to taxes on imported goods created an unlikely alliance between farmers, rural textile manufacturers, and city merchants, culminating in a domestic supply chain that caused colonial America to become increasingly self-sufficient. It was the birth of American manufacturing, and it continued to grow throughout the 18th century.

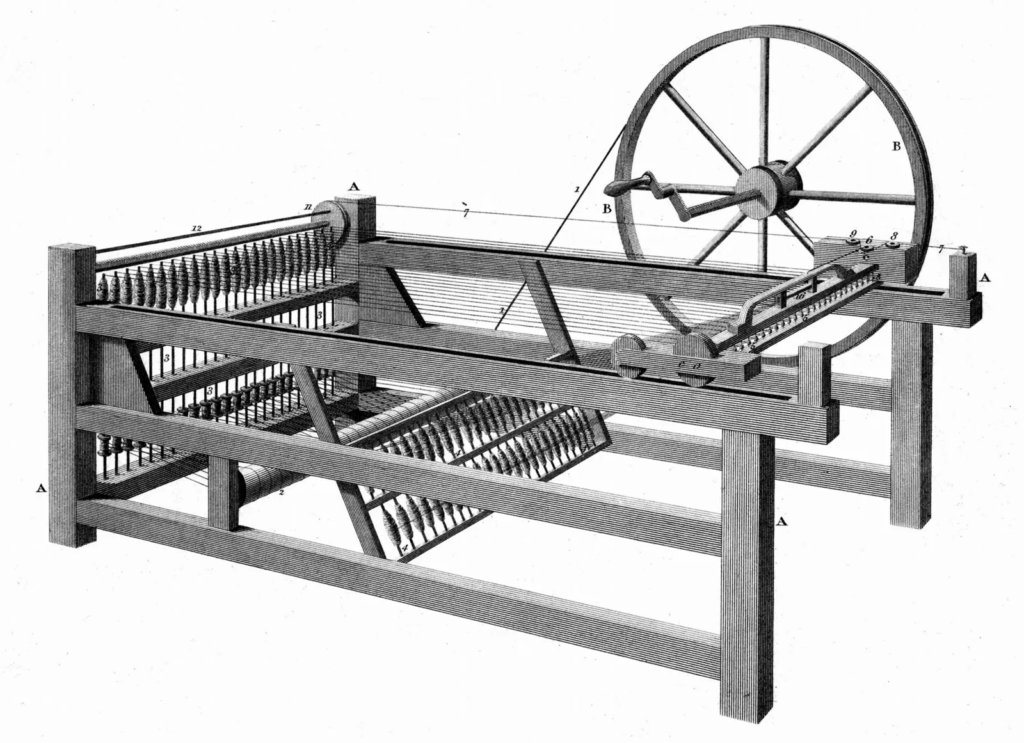

Across the pond, The Intolerable Acts were occurring in England, and the seeds for the industrial revolution began to sprout. One of these seeds, the Spinning Jenny, and the roller spinning frame yanked textiles out of the basement and the artisan’s workshop and planted them on the factory floor. Soon, finer textiles were no longer strictly an indulgence of the wealthy, and New England was flooded with imports of British factory-woven fabrics. New England inventors and entrepreneurs quickly understood their British counterparts’ business and engineering. In 1790 the first American textile mill was established in Pawtucket, Rhode Island.

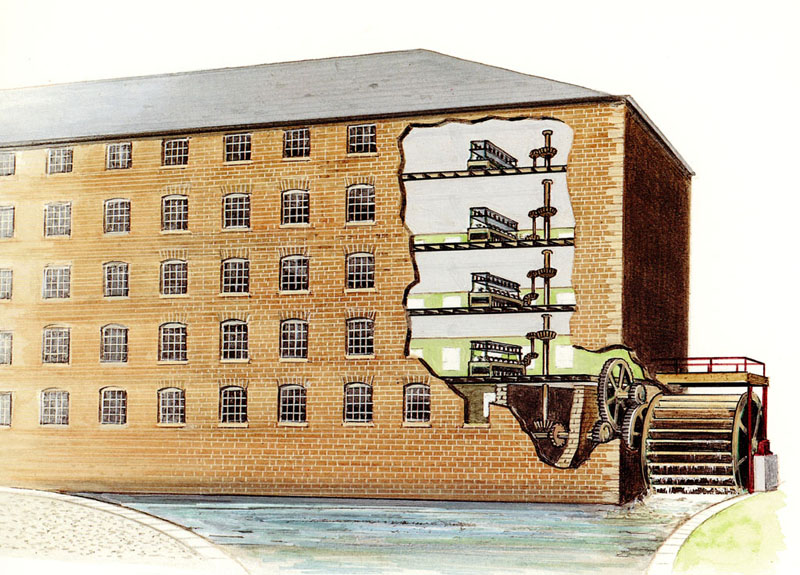

Falling Rivers

Pawtucket, which in the region’s indigenous language means “Fall of Water,” was home to an impressive waterfall and a reliable river. These “Falls of Water” dotted the New England landscape from Maine to Connecticut. Before the steam engine would truly drag the world into modernity, textile mills harnessed natural hydropower. Immigrant and domestically-born mechanics began to innovate further in New England. Methods such as Arkwright’s Roller Spinning Frame took the need for human strength out of the textile manufacturing process.

In 1791, Alexander Hamilton argued that a nation could only be truly free if it had its own developed industry. The reliance on hydropower meant that mills had to be constructed where rivers were reliable, and water fell, making Fall River one of many ideal places. Cities quickly sprang up around mill sites. Seemingly overnight, New England, especially Massachusetts, was bustling with dozens, then hundreds of textile mills. Hamilton’s vision was being realized; by 1840, there were over 700 mills in New England. Even with this significant growth, the boom had yet to occur, and much textile manufacturing was still done “at home.”

Not all aspects of the textile manufacturing process became mechanized at once. When one step became mechanized, the steps before and after became bottlenecks. These bottlenecks were serviced by “freelancers,” often women paid to assist in clearing bottlenecks. This gave New England women one of the first genuine paths toward independence and independently-earned money. Yet, like much of modern freelancing today, the tasks were boring, drudgerous, and non-creative. Eventually, mechanization and innovation solved these bottlenecks. Soon after, textile manufacturing boomed in New England, as did the cities built around the mills.

Tides of Industry

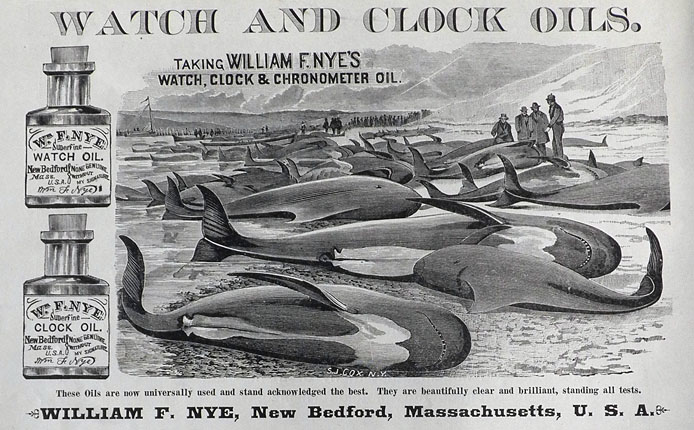

Compounding the industrial strength of the South Coast, these machines were lubricated by whale oil, brought in through the port of New Bedford. As Brown University historian Bathsheba Demuth stated,

“[Whale] fats lubricated a mechanizing country: greasing sewing machines and clocks, and then the cotton gin and power looms. Baleen was useful for its “fibrous and elastic structure,” employed in the manufacture of whips, parasols, umbrellas… caps, hats, suspenders, neck stocks, canes, rosettes, cushions to billiard tables… the energy stored in blubber did not directly power industry – a duty served by waterwheels… but whale products were critical to textile production. A single factory could use nearly seven thousand gallons – three sperm whales’ worth – of oil in a year. Blubber was smeared on sheep before shearing and on fibers to strengthen them for machine weaving.”

-Bathsheba Demuth

Industry on the South Coast and Massachusetts overall was in full swing. The next slate of innovations came not in the form of machines but in labor relations.

The Birth of the Labor Movement

With the birth of American manufacturing came the birth of the modern American labor movement. The first strike occurred as early as 1824 when the women of Pawtucket went on strike to protest wage cuts. Women in Lowell, another major Massachusetts textile city, went on strike for the same reason in the 1830s. Foreshadowing the global industrial economy to rise out of its ashes, the textile industry was subject to a boom and bust cycle caused by poor management and swinging market demand, in which workers were the first to pay the price.

The striking women reminded their employers that they were “the daughters of free men.” Coming from the hardscrabble lives of New England farming families, the women had an idealized vision of a classless American society. One free of the hierarchy and aristocracy their parents and grandparents had just fought a revolution to become independent from. The behaviors of mill bosses and managerial Napoleons did not sit well with them. To the women, it resembled too closely that of British nobility. As Alexis de Tocqueville observed of these women in 1840, “But for equality, their passion is ardent, insatiable, invincible: they call for equality and freedom; if they cannot obtain that, they will still call for equality in slavery. They will endure poverty, servitude, barbarism – but they will not endure aristocracy.”

Labor Organizes

The Lowell-based labor newspaper The Voice of Industry declared in 1845, “We want a peaceful, industrial revolution. A revolution inspired by the principle and love of right instead of passion and might. The result of which will forever ensure to the industrious the fruits of their labor.” Massachusetts was the birthplace and pioneer of the modern American labor movement, and this movement was born in textiles. Spearheaded by women, these strikes were a major domino in the history of American feminism and the road to women’s suffrage. Strikes brought higher wages, shorter work weeks, social benefits, and safer working conditions to the region. The successes of unions in places like Detroit and Pennsylvania owe their success to the path paved by those brave young women in Massachusetts.

Strikes continued as unions became more organized. While the fight was never over, labor won significant battles. These wins helped make the textile industry a reliable path to the middle class that did not necessitate heavy schooling. Despite these gains, hierarchy solidified into normality, especially with the Depression of 1837. With the economy in a downturn, downward pressure was put on the industry, weakening labor and lowering wages. As unemployment rose, many revolutionary women returned to their family farms. The wage-worker system became permanent – albeit on its toes, because of unions.

Part 2 – Boom & Bust

- Outsourced Pt. 3: Collapse | The South Coast’s Textile Industry - October 4, 2023

- Need an Office for a Day? A Week? On-Demand? Look No Further than Coworking Spaces - September 12, 2023

- Outsourced Pt. 2: Boom & Bust | The South Coast’s Textile Industry - July 31, 2023