Outsourced Pt. 2: Boom & Bust | The South Coast’s Textile Industry

This blog post is part two of a series detailing the history of the South Coast’s textile industry and its impact on social capital. If you have not already, please read part one.

Gaining Steam: The Textile Industry Meets the Steam Engine

As the economy sunk in the 1830s, the Industrial Revolution rose. Literally and figuratively gaining steam with the steam engine and the locomotive, creating a new paradigm in economic organization. In the 1840s, New Bedford, Massachusetts, was not a textile city but The Whaling City. Being the home port of over 250 whaling ships and the massive infrastructure built around processing whale oil, New Bedford was one of the wealthiest cities in the world.

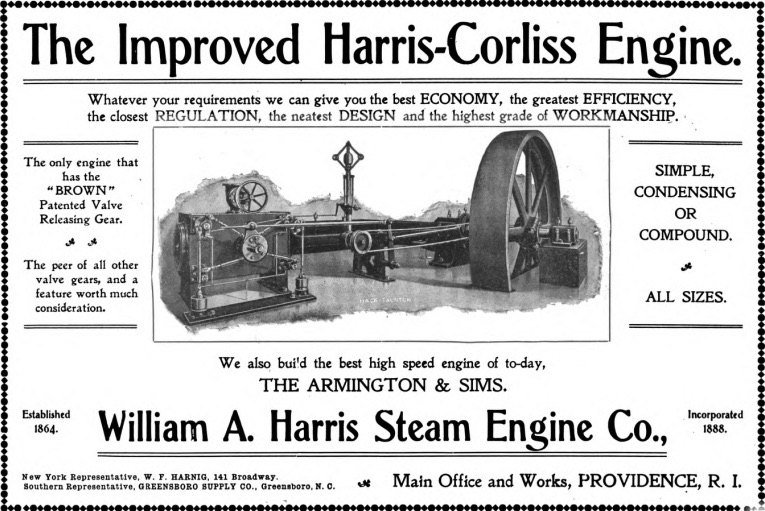

However, as the steam engine was revolutionizing the world, another product of the Industrial Revolution – kerosene, was set to seriously disrupt the whaling industry. The same Industrial Revolution threatening to destroy whaling was also allowing New Bedford to reinvent itself into a textile powerhouse – without the help of hydropower.

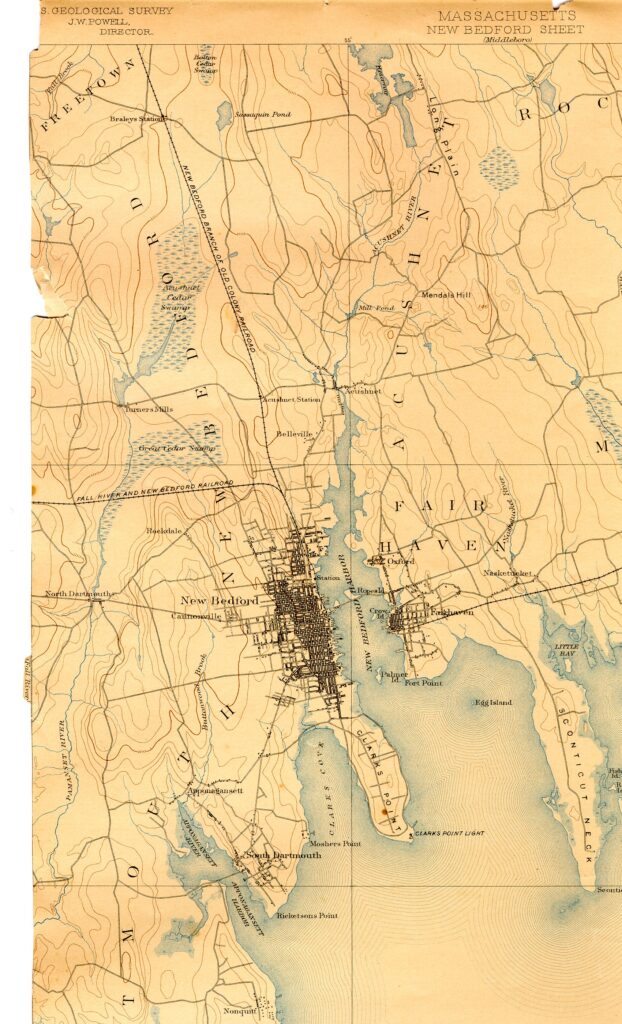

New Bedford, a coastal harbor city, finds its port in the estuary of Buzzards Bay and the Acushnet River. The Acushnet is a calm, gradual river, very different from the roaring falls of other New England mill towns. Until the 1840s, it was impossible to build a textile industry there. However, this all changed with the steam engine. Now mills could be built anywhere. Although whaling was still center stage, New Bedford’s mill development was slow. Toward the century’s end, mills were built in New Bedford with a fervor.

A New Order of Things

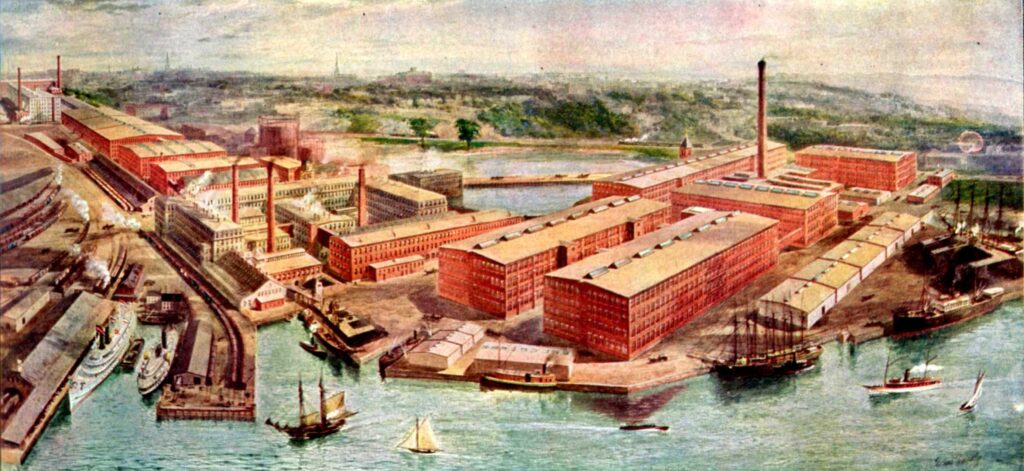

With the steam engine came the train, and the tracks met the sea in New Bedford. Imports and exports could now come in and out by land and sea. With its textile industry situated at this intersection, New Bedford became a model of the modern world. A world defined by the mobility, manufacturing, and logistics revolutions that would plunge the globe into a technological paradigm utterly unimaginable just a generation earlier.

Engineers such as George Corliss of nearby Providence continually improved steam-based textile manufacturing systems’ efficiencies, and New Bedford grew with it. Nearby Fall River, situated with some waterpower, had a limited textile industry. Boston-based financiers at the time were far more interested in the northern and western New England mill towns that benefited from water rushing down off the White Mountains. Fall River remained essentially part of the Rhode Island economy despite being on the Massachusetts side of the border.

However, with the steam engine, the South Coast region of Massachusetts soon exploded in textile development. By the 1860s, Fall River rivaled Lowell. By 1875, it was dubbed the “Spindle City,” and its textile industry was twice that of Lowell. Fall River was home to over 1.8 million cotton spindles working across 30,000 looms in 43 factories. It, too, became a place where train tracks met the sea.

With New Bedford essentially being its sister city, the two transformed the South Coast into an industrial powerhouse, linked by rail and ship to the rest of the United States and the world. By 1920, the textile industry in New Bedford was at its peak. It boasted more than 70 cotton mills employing 33,708 people and running 3.4 million spindles. Thanks to the efforts of unionized labor, textile wages in New Bedford were 48% higher than in the South. In both New Bedford and Fall River, textile schools were incorporated, the buildings of which both Groundwork locations find themselves in today. The heyday would not last. Managers clung to inefficiency and high salaries, finding it more advantageous to run their mills into the ground, outsource southward, and continue to cut wages.

Strike!

During the 1920s, mill owners paid themselves over $47 million in dividends while wages were cut by 30% and factories shut down. After a 10% wage cut was announced in 1928, the textile workers in New Bedford went on strike for six months straight. As the pay cut approached, William Batty, head of the Loom Fixers union and president of the New Bedford Textile Council – a loosely organized coalition of unions, called for a strike vote.

The textile council voted 2,572 to 188 to strike if owners cut wages. When they did, on April 16th, workers marched out of the mills en masse. At first, the strike had an aura of a festival. Spouses and children joined in, music was played, songs were sung, and soup, bread, and candy were handed out. Portuguese fishermen sympathetic to labor provided fish, and Polish bakers baked bread for the strikers. These and other local merchants complained that the decreased wages were constricting local capital flow, hurting their businesses as well.

Even the church, an institution of its own in the South Coast, called the wage cuts unfair. Reverand Linden White declared that private detectives were offering bribes to clergy to preach in their sermons that workers breaking strike was the godly thing to do.

The Textile Mill Committee published a 12-part series by national economist Dr. Norman Ware calling the cuts unnecessary. Local press sided with workers, with The New Bedford Times stating, “Among the newspapers of their own city, [the mill owners] could not find a single editorial comment in their favor.” Even the mill owners themselves were divided. Dartmouth Mills and the Firestone, Goodyear, and Fisk tire plants refused to cut wages.

After three months of silence, industry representatives unleashed a slew of newspaper columns chiding the Police Department for being too lenient on the protests, citing destruction of property and public nuisances.

In response, the police embarked on a series of arrests of labor leaders, and a redbaiting campaign was launched. Strikers were accused of being communists. The strike continued until the city could support it no longer. Eventually, a compromise was struck only after police prevented pickets and the polls.

Losing Steam: Globalism’s Beta Test

There was much to be happy with from the strike for labor. The experience gained from organizing a six-month strike made labor more disciplined and efficient with its future agitation. Many who earned their stripes in the strike spread throughout New England and organized the larger Textile Workers Union of America.

However, by 1929, the strike was over. When the depression hit, mills used the opportunity to flee southward where labor would not bother them, and unions were almost non-existent. What mills remained often had their labor threatened with outsourcing to give in and stay obedient.

By 1938, competition from weak-labored, non-unionized southern mills decimated the industry in New Bedford and only 30 mills remained, and mill employment had plummeted by 77%. New Bedford’s unemployment rate was 32.5%, the second highest in the United States for a city of its size. By the end of the depression, only 13 mills remained.

During these decades, New Bedford was also suffering from the protracted decline of the whaling industry. In 1927 the John R. Manta made the last American whaling voyage out of New Bedford, returning with nothing to show. The Whaling City’s namesake had collapsed, burdening New Bedford with a labor surplus that resulted in increased downward pressure on labor and wages in the textile industry. With unemployment so high from a dual industry collapse, New Bedford’s now infamous criminal element was born out of the first war on drugs: prohibition.

The Beginning of the End

New England mills also owe much of their failure to the refusal by owners and bosses to reinvest in new technologies and keep the facilities up-to-date and competitive, a complaint repeated by union representatives. The biggest mistake on the part of the unions was focusing too locally. Outsourcing to the South would have been less attractive if labor had mobilized nationwide and focused on raising national standards. That all being said, many of the mills that shut down and shipped south were still profitable in the North. Industry was not chasing profit. It was fleeing unions.

In the academic article, Canaries in the Coal Mine: The Deindustrialization of New England and the Rise of the Global Economy, 1923-1975, New York University historian Maura Doherty states, “The myth that ‘Big Labor’ was responsible for the closing of New England’s textile mills distorts the power that unions actually employed and deflects attention away from corporate strategies to discipline labor and maintain hegemony.”

Even when labor gave concessions, they were still blamed, and jobs were outsourced anyway. By 1949, outsourcing textiles had brought New Bedford’s unemployment rate to 18%, Fall River’s to 20%, and Lowell’s to 20%. During the 1950s, industries adjacent to textiles were declining rapidly as well. By 1958, the leather industry had lost 10,000 jobs since the outbreak of World War II.

Fall River was the epicenter of New England’s textile industry. Of a population of 110,000, 15,000 were directly employed in textiles – a larger proportion than any other mill city in New England. The Textile Workers Union of America (TWUA) represented these workers. During the 1920s, bungled management, obsolete machinery, and the draw of low-wage southern workers caused Fall River’s textile industry to collapse. Between 1925 and 1930, over a third of the city’s textile workers were laid off, and the city of Fall River, facing the destruction of its tax base, went into bankruptcy.

Check Out Part 3: Collapse

- Outsourced Pt. 3: Collapse | The South Coast’s Textile Industry - October 4, 2023

- Need an Office for a Day? A Week? On-Demand? Look No Further than Coworking Spaces - September 12, 2023

- Outsourced Pt. 2: Boom & Bust | The South Coast’s Textile Industry - July 31, 2023